A Practical Showdown: Feature Engineering vs. CNNs for Drum Sound Classification

– ArtXTech

The Great Audio Re-Validation: Why Your Bloated Deep Learning Model is a Shambles

Abstract: The Sequel No One Asked For (But Everyone Needs)

Last year, I dug into a “ruled line detection” project and stumbled upon a truth that felt like a glitch in the Matrix. Traditional models with proper Feature Engineering can absolutely demolish End-to-End Deep Learning on small datasets. I finished that class asking if the industry’s obsession with “Deep Learning for everything” was just a massive, resource-hungry hype cycle.

Well, I’m back. This time, I’m taking that hypothesis into the audio domain. I reckon if the “simple is better” rule held for visual pixels, it’s got to hold for drum hits. We’re pitting a refined, Feature-Engineered approach (Random Forest, SVM, KNN) against an End-to-End CNN fed on Mel Spectrograms. It’s the classic battle: Classical model with my bloody tears vs. The GPU’s brute force.

Introduction: Beyond the Hype

Well, let’s review what I was doing in the middle of 2024.

Screaming at my monitor, hair-pulling frustration, the whole bloody shambles. You know the drill. Another project, another descent into the painstaking process of trying to teach a machine to hear the difference between a kick drum and a snare. Why? Because I’m a glutton for punishment, apparently.

And because my last project that I proceeded in the late 2024, wrestling with scanned images, left me with a nasty suspicion, I’m like- these days, everyone wants to throw a massive transformer at a problem that could be solved with a bit of math and a cold beer.

It’s an intervention. An intervention for an industry that’s become obsessed with massive, ethically-dubious generative models while forgetting the absolute art form of proper feature engineering. I’ve spent a decade in the feature factory as a senior dev, debugging the unholy mess spat out by junior devs who think LLMs is a magic wand. It got so bad I literally escaped reality and buggered off to grad school.

I’m still haunted by my previous project where I tried to strip ruled lines from notebook sketches. Everyone said “Use a CNN, mate!” but the CNN struggled with the small dataset (under 2k samples). Meanwhile, a humble KNN with some edge-density features performed like a bloody legend.

Now, I’m taking that turning it into a controlled experiment. My mission: to prove that a cleverly crafted traditional model can absolutely demolish a lazy, end-to-end DL on a small, well-defined audio dataset. In the world of beatmaking and Music Information Retrieval (MIR), classifying a drum hit—Kick, Snare, Tom, Overhead—is bread-and-butter stuff.

I’m here to prove that the industry’s “AI Hype” is often just a fancy way of wasting tokens. We’re re-validating the “Sophisticated Feature Engineering > Brute Force” law.

1. Objective & Hypothesis

This document details a practical research project I conducted as part of my Master’s studies. The objective was to solve a common challenge in audio library management: accurately classifying individual drum sounds (kick, snare, hi-hat, etc.) from a small, custom dataset. Wait, didn’t you mention that you have handled the large dataset? Well, sort of. After reviewing spatial sound analysis roughly, I found that more than half of them were non-relevant to this specific project. So I only selected dataset, almost like- don’t know, like 1/10?

The core hypothesis was to test whether a meticulously crafted Feature Engineering pipeline could match or outperform a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)—a common deep learning approach—in a resource-constrained, real-world scenario. The goal was not just to achieve high accuracy, but to build a solution that was also interpretable, computationally efficient, and scalable.

2. Methodology: A Two-Pronged Attack

I designed and implemented two distinct pipelines to tackle the classification task.

The Dataset:

The foundation for this experiment was a curated dataset comprising several hundred individual drum one-shot samples, meticulously labelled into distinct classes.

For the source of truth, I didn’t just scrape some random junk. I grabbed public datasets and supplemented them with samples from my own DAW (Logic Pro). I manually sorted these into four buckets:

- Class 0: Cymbals (The sizzle)

- Class 1: Kick (The thump)

- Class 2: Snare (The crack)

- Class 3: Toms (The ring)

I kept it to four classes because, let’s be honest, distinguishing between a “Mid Tom” and a “Floor Tom” depends more on the drummer’s mood than a universal frequency constant.

The Setup: Two Kinds of Drum Kits, One Big Question

First things first, let’s talk data. Not all datasets are created equal, and this is where most projects fall apart before they even begin.

Scenario: The “Single-Hit” Dream.

/bloody_drum_samples/

├── kicks/

│ ├── fat_kick_01.wav

│ └── clicky_kick_02.wav

└── snares/

├── tight_snare_01.wav

└── ...

If your data looks like this, you’re laughing. The folder name is the label. No mucking around with MIDI files, no painful audio slicing. You just load the .wav, grab the folder name, and you’re off to the races. Simple. Elegant. The way things should be.

We’re sticking with this Scenario. Because I want to test the models, not my sanity.

Approach A: The Interpretable Feature Engineering Pipeline

This approach follows a classic, “white-box” machine learning methodology. The core principle is to use domain knowledge to extract meaningful numerical features from the audio, then feed this structured data into a traditional classifier.

The “Feature Engineering” Bit: Turning Sound into Numbers (This is where the magic happens)

Alright, so how do you explain a kick drum to a machine that only understands numbers? You can’t just feed it the raw waveform. That’s like trying to teach Shakespeare to a goldfish. You have to describe it. You have to give it characteristics. This, my friends, is Feature Engineering, and it’s a goddamn art form.

Here’s the Mermaid diagram of my brain trying to figure this out, probably at 2 AM with tears welling up.

graph TD

A["Raw Audio (.wav)"] -->|Librosa Extracts...| B{Feature Groups};

B --> C["Time-Domain: How LOUD is it?"];

B --> D["Frequency-Domain: How BRIGHT is it?"];

B --> E["Timbral/Perceptual: What's its bloody CHARACTER?"];

C --> F["rms_mean: The average punchiness"];

C --> G["zcr_mean: The sizzle and noise"];

D --> H["spectral_centroid_mean: The brightness knob"];

D --> I["spectral_bandwidth_mean: The richness and complexity"];

E --> J["mfcc_[1-20]_mean: The bloody acoustic fingerprint"];

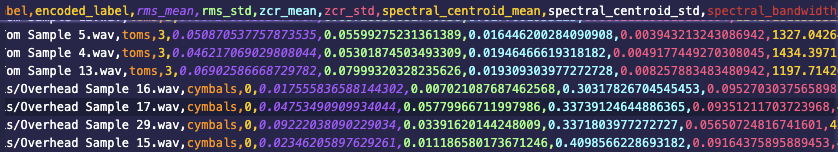

After painstakingly extracting all this, we get a beautiful, clean drum_sound_features.csv. This isn’t just data. This is a story, told in numbers.

Step 1: Automated Feature Extraction (Python & Librosa)

Instead of manual listening, I developed a Python script to programmatically analyse each audio file. The powerful Librosa library was used to extract a rich set of acoustic features known to be relevant for percussive sound analysis, including:

- Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCCs): To capture the timbral and textural qualities of the sound.

- Spectral Contrast: To identify the relative distribution of energy across the frequency spectrum.

- Chroma Features: To represent the tonal characteristics.

- Zero-Crossing Rate: A simple but effective indicator of a sound’s “noisiness.”

- RMS (Root Mean Square): To quantify the overall energy and loudness.

Step 2: Model Training (Scikit-learn)

The extracted features were compiled into a structured dataset (a Pandas DataFrame). I then trained and evaluated several powerful, interpretable classifiers from the Scikit-learn library, primarily:

- Support Vector Machine (SVM): Excellent for high-dimensional data and clear margin separation.

- Random Forest: A robust ensemble method that prevents overfitting and provides feature importance metrics.

- Gradient Boosting: I used GridSearchCV with StratifiedKFold because my dataset is small, and I didn’t want any “Data Leak” shambles ruining my results.

Before moving on, shall we review EDA for a sec?

I ran an ANOVA F-Score to see which features actually mattered. Unsurprisingly, Spectral Centroid and ZCR were the MVPs. RMS Energy (Loudness) was actually a bit of a dud—turns out, volume doesn’t tell you much about character.

I performed a PCA (Principal Component Analysis) on the features. Look at the clusters! The boundaries are so clean you could cut yourself on them. This confirms that my feature engineering turned a “messy” audio problem into a simple “geometry” problem.

Approach B: The Deep Learning “Black Box” Pipeline

This approach represents the modern, end-to-end deep learning methodology. The philosophy here is to let the model learn the relevant features on its own, directly from a visual representation of the audio.

-

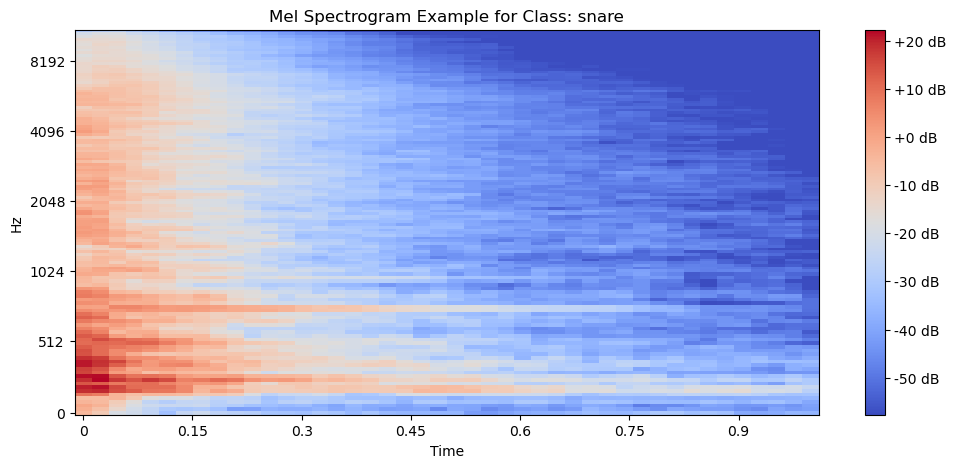

Step 1: Data Pre-processing

Each audio file was converted into a Mel Spectrogram. This is a 2D image that visually represents the spectrum of frequencies in the audio over time, making it an ideal input for image-based neural networks. -

Step 2: Model Architecture & Training (TensorFlow/Keras)

I designed and trained a standard Convolutional Neural Network (CNN). The architecture consisted of several convolutional and pooling layers to detect patterns in the spectrograms, followed by dense layers for the final classification.

3. Results: The Showdown

The results were compelling and ran counter to the common “deep learning is always better” narrative.

The Showdown: SVM (The Old Master) vs. CNN (The Cocky Upstart)

So we have our beautifully enginered features. Now for the main event.

- In one corner: The Traditional Models, spearheaded by the Support Vector Machine (SVM). We feed it our handcrafted features. It’s like giving a master chef the best possible ingredients.

- In the other corner: The Convolutional Neural Network (CNN). The “end-to-end” solution. We don’t give it our features. We just give it the raw sound, converted into a picture (a Mel Spectrogram), and tell it to figure it out on its own. It’s like giving a clueless apprentice a pile of random groceries and hoping for a Michelin-star meal.

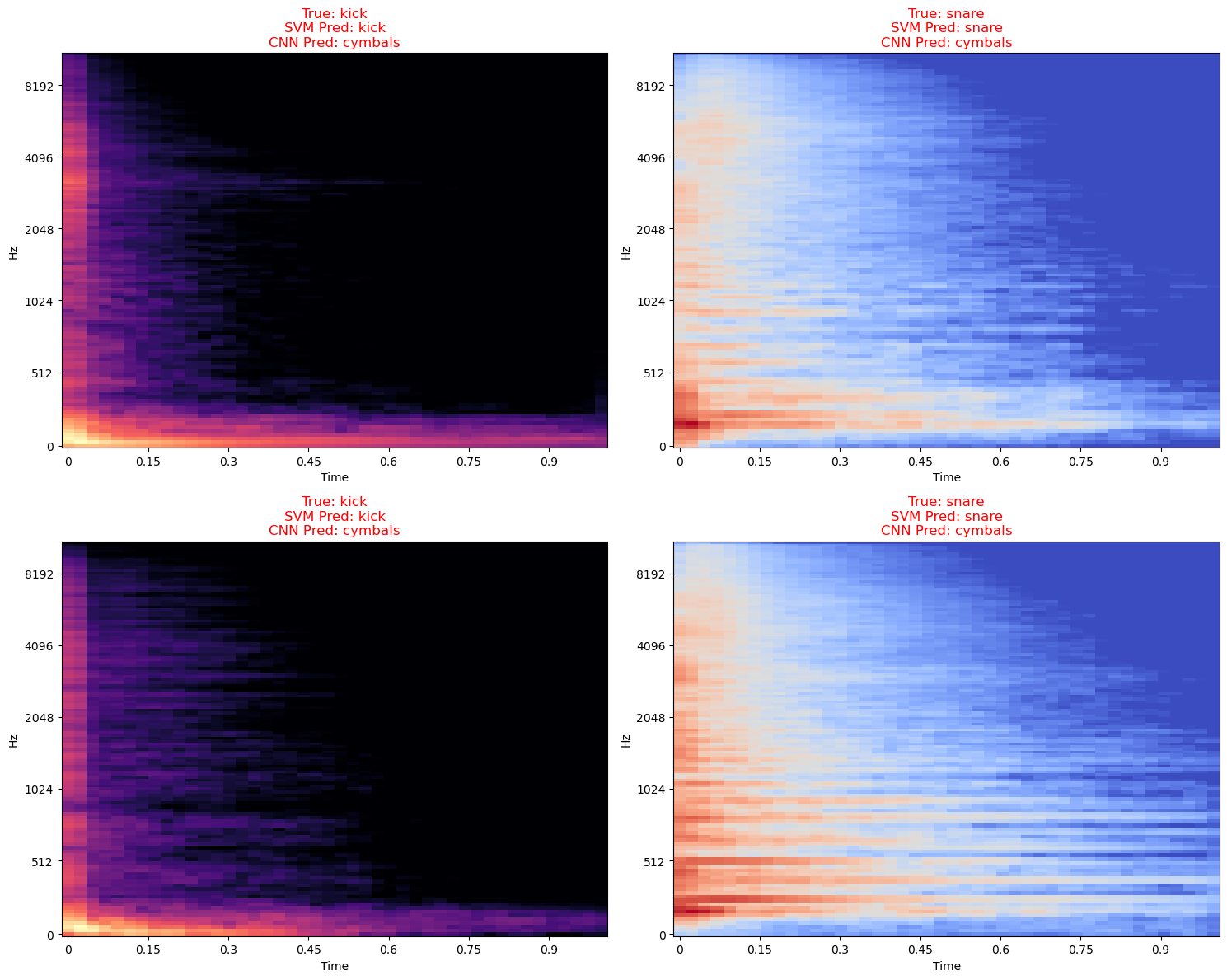

The results? It wasn’t even a contest. It was a bloody massacre.

| Model | Accuracy | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|

| SVM (RBF Kernel) | 1.00 (Perfect) | 1.00 |

| Random Forest | 0.975 | 0.974 |

| CNN (The “Future”) | 0.275 (A disaster) | 0.2757 |

The SVM, armed with our carefully crafted features, perfectly classified every single sound. The CNN, left to its own devices with a small dataset, had a complete meltdown. It couldn’t tell a tom from a hole in the ground. The confusion matrix showed it didn’t correctly identify a single ‘Tom’ sample. Not one.

Why did the CNN fail?

Overfitting. Plain and simple. The CNN has 1.4 million parameters. 93% of them are in the first Dense layer. It didn’t learn the “laws of sound”; it just memorized the noise in the training set. It’s a “glass cannon”—looks powerful, but shatters the moment it sees a file it hasn’t met before.

4. Conclusion & Strategic Takeaway

While DL could be incredibly powerful, this project proved that for specific, well-defined tasks with limited data, a strategic Feature Engineering approach offers significant advantages that are critical in a production environment:

-

Interpretability is a Feature, Not a Bug: The feature-based model allows us to understand why a decision was made. We can see exactly which features (e.g., “high spectral contrast” and “low RMS”) are strong predictors for a “snare.” This is crucial for debugging, fine-tuning, and building trust in the system. It’s a “white box,” not a “black box.”

-

Computational Efficiency: The Feature Engineering pipeline was significantly faster to train and required far less computational resource than the CNN. This translates directly to lower operational costs and faster iteration cycles in a business context.

-

The “Right Tool for the Job” Philosophy: This experiment reinforces my core professional philosophy: don’t just throw the biggest, most complex tool at a problem. True architectural elegance comes from deeply understanding the problem domain and designing the most efficient, direct, and maintainable solution. Sometimes, that means choosing a scalpel over a sledgehammer.

This project is a tangible example of how I bridge the gap between creative assets, data science, and scalable engineering to build intelligent systems that truly work

Conclusion

Don’t blindly follow trends. By analysing specific acoustic features (RMS, ZCR, Spectral Centroid), I established a data-driven taxonomy logic that classifies drum sounds more accurately than heavy models. This mindset ensures I can “sanity-check model choices” effectively.

We are currently in an AI “arms race” where companies are scraping every bit of human data just to feed these hungry, inefficient models. My experiment(twice now)has proven that smaller, smarter, and more ethical approaches often win.

Instead of obsessing over bigger datasets, we should be obsessing over better engineering. A bit of domain knowledge and a well-tuned SVM can do more for your product than a billion-parameter model that can’t tell a Snare from a Kick.

The Epiphany: It’s Not the Size of Your Model, It’s How You Use Your Data

So, what’s the takeaway from all this?

This report is proof. It proves that in the real world, with limited, messy data, domain knowledge and clever feature engineering aren’t just important—they are everything. A well-understood problem with well-designed features will always, always outperform a black-box behemoth that’s just hoovering up data without context.

My personal journey from a burnt-out senior dev to a grad school refugee wrestling with this stuff isn’t a tangent; it’s the whole point. The industry is drowning in AI Slob, and it’s creating more problems than it solves. We’re losing the art of problem-solving, the joy of the deep dive, the sheer passion of crafting an elegant solution from first principles.

This project started as a simple classifier. It ended as a philosophical standpoint. The future isn’t about building bigger models. It’s about being smarter scientists, more creative engineers, and more thoughtful artists. It’s about understanding the why, not just the how.

As a dev who actually loves this stuff, I hate seeing “AI” become a dirty word because current trend suits keep chasing “size” over “soul.”

And my work proves it. Now, if you’ll excuse me, I reckon it’s time for a beer. Until then, see ya-

Related Articles

EN-GameToAudioDesign

EN-Memo-AudioCategorisingTagging

EN-K-Pop-Live-Band-Rework